The American Civil War was the bloodiest struggle in American history and the estimated 620,000 deaths of soldiers between 1861 and 1865 are roughly equivalent to the combined American casualties in the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Mexican War, Spanish American War, World War I, World War II, and Korean War.

Compared to the size of the American population, the rate of death during the Civil War was six times higher than during World War II. In the United States today, a similar incidence of around 2% would result in six million fatalities. One in five southern males who served in the Confederacy died during the Civil War, which was at a rate three times higher than that of their Yankee counterparts. Due to poor sanitation and a lack of understanding regarding the transmission of infectious diseases like typhoid, typhus, and dysentery, twice as many Civil War soldiers died from sickness as from battle wounds.

In addition to soldier deaths, the war also killed a significant number of civilians as battles raged across cities and farms. According to Civil War historian James McPherson’s estimate of 50,000 civilian deaths during the conflict, the South experienced a higher overall mortality rate than any other nation in World War I and every other region in World War II, with the exception of the area between the Rhine and the Volga. The American Civil War caused destruction that was frequently assumed to be reserved for the era of advanced technology and inhumanity that would come later.

Additionally unexpected and unprecedented were the conflict’s size, length, combat size, and amount of victims. Many people referred to what both the Union and the Confederacy produced as a “harvest of death.” By the middle of the war, it appeared that “almost every household mourns some loved one lost” in the South. Loss became routine; people no longer experienced death individually. For the duration of the conflict, the threat, the nearness, and the reality of death became the most frequently encountered situation. The effect of these deaths caught the nation off guard, leaving them unsure of what to do with the dead that littered the battlefields, how to grieve for so many lost, how to remember, and how to comprehend.

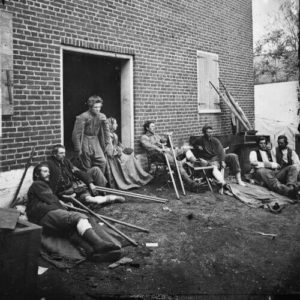

The logistical challenge of burying soldiers after a battle was the most pressing death-related issue. Particularly in the aftermath of engagements like Antietam or Gettysburg, where thousands of dead covered the battlefield, armies were unprepared for the size of the task that lay before them. At Antietam, for instance, there were 23,000 men dead or injured after just one day of fighting in addition to an incalculable number of horses and mules. The armies on both sides lacked grave registration units, official identity badges for soldiers, a proper notification procedure for the slain’s relatives, and an ambulance service.

In such conditions, tens of thousands of soldiers perished without being identified, and tens of thousands of families were left in the dark regarding the whereabouts, causes of death, and final resting places of their loved ones. At least half of those who died during the Civil War were never found. These realities grew more unacceptable as the war went on, and Americans battled against such loss and dehumanization in both formal and informal ways. Soldiers searched for, buried, and remembered their fallen friends. Businesses produced and sold identity disks for soldiers. Before particularly risky meetings, the men personally attached their scrawled names to their uniforms.

As a result, volunteer groups like the U.S. Sanitary Commission were formed. They focused their efforts on creating records of battlefield burials, compiling lists of the dead and wounded from hundreds of Union hospitals, and assisting families in finding the missing and, for those who could afford it, shipping embalmed bodies home. After battles, families flocked to the scene to look for lost or injured loved ones, deliberately seeking information that would otherwise be out of reach for them in an effort to fill what one northern observer described as the “dread hole of uncertainty.”

The war’s end in the spring of 1865 provided an opportunity to care for the dead in ways that had previously been impractical. Clara Barton was among the first to take advantage of the end of hostilities by opening an office of Missing Men of the United States Army in Washington, D.C. to act as a clearinghouse for information, motivated by the same humanitarian motives that had led her to nursing during the war. By the time she shut it down in 1868, she had gathered data on 22,000 soldiers and received more than 68,000 letters.

0 Comments